Climbing the North Buttress of Outpost Peak in Tonquin Valley, AB

It began, as all good misadventures do, with a misunderstanding. “Oh, that doesn’t go,” the mountain guide told us, as we stared up at the North Buttress, a sharp prow of rock jutting from the side of Outpost Peak. We weren’t speaking of the Buttress itself, but our planned descent route: traversing the summit of Outpost Peak to the neighbouring Memorial Peak, and from there, a gentle ridge to the floor of the valley. Which now, with 17 kilometers of hiking trail already under our belts, backs aching from too much weight, and on day one of a four day trip, we find out is no longer viable. Hmmm.

This weekend, we were on a tour of the Tonquin Valley, just southwest of Jasper, Alberta – the final leg of our Rockies road trip. We had hiked and camped at the beautiful Lake O’Hara, mountaineered behind Moraine Lake in the shadow of Mt Fay, and now were finishing off our stay in wild rose country with a four-day trip to the remote Tonquin Valley, made famous by the towering rock formation known as the Ramparts, and the somewhat popular through-hike to view them. We found out pretty quickly once we arrived in Jasper, however, that ‘popular’ is a relative term. We’d fought crowds at Moraine Lake, stood in lines in Banff, and gaped at the parking lot of the Athabasca Glacier on the Icefields Parkway, and so feel qualified to tell you: Tonquin Valley is not popular. With our trip scheduled to coincide with the August holiday weekend, we expected hoards of backpackers on the hiking trails. Not so. And with a prominent mountaineering hut run by the Alpine Club of Canada – the Wates-Gibson Hut – onsite so close to the Ramparts, we expected prolific amounts of information to be available on the nearby mountaineering routes. Also not so. In fact, we were positively starved for beta (information about the climb) as we did our pre-trip research. Nothing on conditions, no recent trip reports… Even a trip to the local climbing shop in Jasper yielded nothing. “That’s part of the fun,” the man at the shop told us when we inquired which guidebook might contain route descriptions. “It’s how the old-school mountaineers used to do it. Just go out there and figure it out.” Right. For us budding alpinists (and raised on the internet no less), the thought of going in blind was mildly anxiety-provoking, but here we were, at the feet of the mountains, and not about to call off our trip. We armed ourselves with a couple screenshots and a few pictures and notes we found online, packed our bags, and hit the trail.

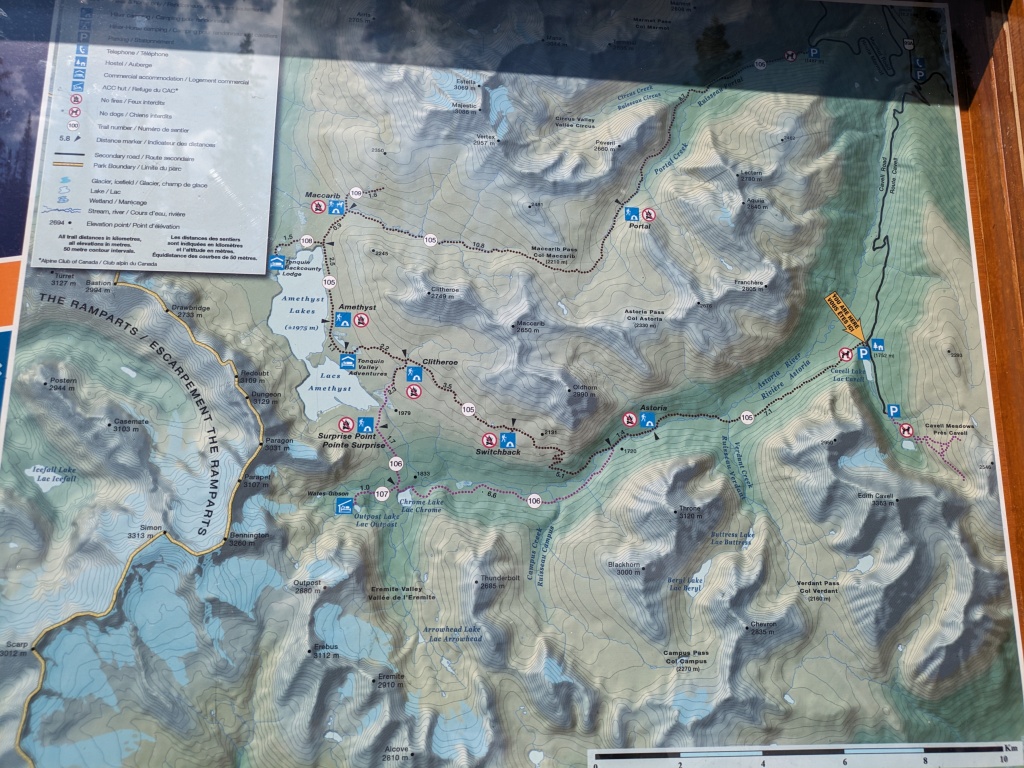

The Tonquin Valley is commonly done as a through-hike between two trailheads: the Astoria River trail beginning across the street from the Edith Cavell Hostel, and the Maccarib (Portal Creek) trailhead. It’s a horseshoe-shaped trail, with the majestic Ramparts in the middle. Seven backcountry campsites exist along the way, as well as the Wates-Gibson Hut, allowing backpackers to complete the hike in anything from 2-5 days. As the through-hike was not our objective, we elected to stay at the hut, which supplies cooking equipment and mattress pads, and thus allow us to save some weight and leave room in our bags for climbing equipment. After cruising the sparse information we could find online, we were there to attempt to climb two mountains: Outpost Peak, looming directly above the hut, and Paragon Peak, on the far edge of the Ramparts formation. Both involved some technical climbing, and maybe the odd rappel, but our reading led us to the conclusion that there was no snow nor ice we’d need to travel, and so we elected to leave our ice gear (crampons, axes, and screws) behind.

Our first day in the Tonquin Valley consisted of only the approach to the Hut. Wates-Gibson lies at the very back of the horseshoe, next to the Ramparts, at the end of a 17 km hike. While we found the trail to be muddier and swampier than expected (although I did receive a warning that the wilderness around Jasper is famously swampy), fortunately, there was not much elevation gain. Our backs and feet were pretty unhappy as we finished our day at the door of the cute log cabin however. Since we saved weight on cooking and sleeping gear, we decided to bring some decent food to the hut to make use of the propane stoves, frying pans, and French press (although, desperate as I was to try, I could not find a way to make use of the propane oven; all the cookie mixes I looked at in the grocery store needed eggs, which I had no way to transport).

The Wates-Gibson hut is a spacious log cabin, and is pretty similar to what we’ve come to expect from the Alberta ACC huts, with the exception of the fancy oven in the kitchen and an epic two-storey stone fireplace. The hut has essentially three rooms: a large common room filled with tables and chairs, plus the fireplace, a decent-sized kitchen, complete with all the cooking and eating utensils you could possibly need on your backcountry trip, and a roomy loft upstairs with sleeping pads, warmed by the stone fireplace running through it. Propane is supplied for cooking and lighting, as well as firewood for the colder months. An outhouse is behind the hut, and the common room is filled with games, books, and old mountaineering history. As it sleeps about 26 people, we expected the hut to be full on a hot and sunny holiday weekend. While we weren’t alone, there were never more than two or three other groups there however, maybe around 10 people total, and only one other set of mountaineers – two older men with a professional mountain guide. The low volume of people we met as we hiked during that weekend confirmed our growing suspicion: there is so much mountain to explore in the Rockies that simple Tonquin Valley is not getting nearly the traffic it deserves.

We settled into the hut at the end of day one, discussing our plans for the climb up Paragon tomorrow. Shortly after our arrival, we met our hut-mates for the next few days: the mountain guide and his two clients. They had just returned from a 12-hour day climbing the buttress on Outpost Peak, one of our planned routes, and were hoping to climb Paragon Peak the following day. As no one was eager to share the mountain (and all the associated rockfall that comes with that), we agreed to swap objectives and climb Outpost the following day instead while they climbed Paragon. This had the added benefit of allowing us to collect all the details of both climbs and current conditions from this professional mountain guide. EXACTLY what I was missing. Score.

But a quick conversation soon deflated my hopes. The guide told us that our descent route would not work, not without ice gear (and you’ll recall that I chose food over ice gear). He had led his clients up the North Buttress, a 7-pitch rock climbing route up a series of 3 extremely vertical towers, and then straight down a snowy ramp onto the glacier on the west side of the peak, and from there down into the Frazer Glacier basin. Chris and I regrouped after our conversation, taking a walk around Outpost Lake to stare at the mountain’s flanks and talk tactics. A search of the hut had fortunately yielded some additional beta in the form of photocopies of route-descriptions from a guidebook (one that we DID NOT purchase from the climbing store in Jasper, as the man at the store didn’t seem to have a clue that it existed, despite it happily existing on a shelf about 5 feet from his right elbow). A plan for an alternate, hopefully rock-only descent from the summit was formed: the southeast ridge, a potentially gentle ridge leading to a glacier on the east flank, which, with any luck, could be bypassed. From there, hopefully mild terrain would lead into the Eremite Valley, where an old hiking trail existed, and hopefully, a still intact bridge over Eremite creek (some old comments in the hut guest book led us to believe that the bridge was out). Lots of “hopefully’s” did not leave me feeling great about our route selection though. “Maybe it goes” is not a mental space you want to sit in while mountaineering, trust me. Even the guide felt pretty worried for us when we told him our alternate route plan, offering to lend us his group’s crampons. Another red flag… Our scouting walk around Outpost Lake did little to calm my nerves. We had hoped to walk far enough east to get a look at the SE ridge and possibly even get eyes on the glacier behind on the southeast face, to see if we could trace a route through. No luck. It was impossible to see that side of the mountain without getting up into the Eremite Valley, which we would not be doing a half hour before sunset.

Feeling nervous about the next day, we returned to the hut to make dinner. As we ate, we caught up more with the guided group on their trip and our plans for the following day. It was here that we came to realize our misunderstanding. The climb had taken them so long (groups of 3 are often slower, and guides are required to short-rope clients on absolutely anything that might even be vaguely unsafe, meaning they spend a lot of time messing around with ropes), that once they reached the top of the buttress, the guide was simply looking for the quickest way to get his team off the mountain, which happened to be straight down onto the ice of the glacier. This worked well for them, with crampons and axes, but wouldn’t work for us. However, we reviewed some summit photos from the previous day with the guide and confirmed that our original plan, a traverse on the rock ridge between Outpost and Memorial Peaks, then a descent down the easy west side of Memorial, then a rocky walk back to the hut (a route we’d noted several times as ‘recommended’ online), would in fact work. “That ridge will definitely go,” he told us confidently. “No snow up there. That’s a better plan than the SE ridge descent”. With our confusion cleared, and some fresh, professional eyes on our route choice, we felt significantly better about tomorrow’s adventure as we headed off to bed. Little did we realize the value of the alternate plan at the time…

A quick pre-dawn breakfast and some last-minute packing saw us out of the hut at 5:30 am, just as the sky was lightening. We followed a well-marked trail directly south of the hut towards the Frazer Glacier basin, and soon parted ways with the guided group, who were off to climb Paragon Peak. The trails leads through the trees for about 10-15 minutes before depositing you in a rocky moraine. From here, we made for a faint path that we could see rising on our left up a steep scree slope to the base of the North Buttress of Outpost. As this path petered out, we reached a series of grassy ledges. Next, you are supposed to trend hard left along the first ledge directly to the skyline ridge, then move up through easy 3rd class scrambling to the notch at the base of the technical rock climbing. What we did, however, was get some tunnel vision on gaining elevation. When we hit the ledges, we climbed all of them, right through some slightly sketchy, mossy scrambles. As we neared the top of the ledge system, and trended left to reach the skyline ridge, we then encountered an incredibly steep and exposed slope of pure ice – 100% not crossable, even with crampons.

Here, as we realized our mistake in routing-finding, we committed another: we didn’t want to expend the extra effort to downclimb, then climb all the way back up the ridge to our current elevation. Instead, we looked above, eyeing a dubious weakness that ran through the rock from a tower above our current position, above the ice-gully, and to the notch at the base of the Buttress route. We thought we’d simply climb up to the start of the weakness to have a better look and see if it would go. The climb up was perhaps 4th class scrambling, but mossy and dirty. When we reached the top of the tower, we could see clearly that we had deluded ourselves. That ‘weakness’ was definitely not something we could safely cross. Our only option was down. D’oh! As the climb up had been dirty, and as we found a great boulder up top, we elected to sling some tat around it and rappel. I led the way, and with a bit of route-finding, our 60-meter rope left me in a steep scree gully that we could descend. As luck would have it, a few meters down, I found another great boulder, and set up some tat for a second rappel. This saved us some dusty, steep, and miserable descending. Unfortunately, after our ‘scouting mission’, plus the two rappels and subsequent descent of the ledge system when we found ourselves back on track again, we had wasted about 3 hours.

Pushing down the frustration of the morning and eyeing the aesthetic line of the North Buttress with its three towers rising overhead, I still felt compelled to complete our route instead of turning around and heading back to the hut. Turning to Chris, I asked, “Are you up for an epic?”. The second critical component of a misadventure. Chris, always game for more suffering, responded in the affirmative, and we were off. We chose to press on for a number of reasons: we were very close to the base of the actual route, we had a ton of daylight left (the sky stayed light until about 10 pm up there), Chris and I generally move pretty fast in the mountains, the weather forecast was absolutely flawless that day (sunny, no clouds, low wind), and we were well-equipped with what we needed for a long day (enough food, water, and warm layers, as well as communication, rescue, and first aid gear). So it was that after about 5.5 hours enroute, we found ourselves scrambling to the notch at the base of the first tower.

The rock climbing on the North Buttress is quite straightforward, with unusually easy route-finding for an alpine climb, and even a brief description on Mountain Project. The climb is spread out over 7 suggested pitches on 3 towers to the top of the buttress. There are no bolts, pitons, or other leftover hardware of any kind. We climbed the route in 6 pitches with a 60 m rope (3 on the first tower, 2 on the second, and 1 on the last), but it could easily be climbed in 5 pitches with a 70 m rope (the guided group told us they climbed it in 9 pitches!). The hardest moves are contained in the first portion of the first tower, with moves up to 5.6 (although it’s a steep, loose, Rockies 5.6). None of the route is hard climbing, although the whole thing is exposed, airy, and very vertical for easy 5th class. A few moments are somewhat thin on feet, especially in mountaineering boots, but much of the climb is in the 5.0-5.4 range. The challenge of the climb is gear anchors and placement, and fighting against loose rock. Test all holds (both hands and feet) before committing, and sometimes you’ll have to simply accept a large runout as there will be nowhere stable to place protection. The position of the climb is excellent, with several very airy sections right on the arete. Routefinding is easy – simply stay on the ridge, or if that looks tricky, climb a bit left or right to bypass difficulties. For gear, the recommendation is a standard alpine rack to 3”. I personally skipped the 3” cam and brought doubles to 1” to have some extras for long pitches and gear anchors. You’ll definitely place a 3” if you brought it, but I was fine without it. If I was to climb the route again, I’d consider bringing instead singles to 3” with a couple microcams thrown in. Long draws are essential here, and you’ll want lots of long sling/cord for gear anchors.

Surmounting the final epic pitch on the third tower left us on top of the North Buttress. As we stopped to finally eat something, pack up our climbing gear, and soak up some views, a disturbing reality began to make itself known: the traverse to Memorial Peak, our planned descent route, most certainly did not go. You’ll recall that this was the source of our earlier confusion regarding route planning, and only after we had assurances from the guide up there the previous day did we decide to commit to the route. While a crown of rock could be seen against the skyline (perhaps leading the guide, with only a cursory glance, to think it was a reasonable traverse on rock), on close inspection, we realized that the visible rock was a cliff, with the other side covered in a steep, cracked wall of thin ice. Even with crampons (which we did not have), that ice did not look safe to attempt.

Anxiety mounted as we completed the 45-minute traverse from the top of the buttress to the true summit of Outpost. The more we stared at Memorial and the wicked glacier below, the more we realized that all our hopes of a safe descent now rested on the feasibility of the southeast ridge route – our original backup route, the one we were nervous about due to unknowns regarding the glacier and Eremite valley river crossings. I felt a bit helpless as we scrambled the boulders, staring at the impossible Memorial Ridge and wondering if we could pioneer some crazy rock route around the backside. Or was this the day we finally had to activate our inReach and call for help? I shied away from the thought; the embarrassment and defeat would be hard to stomach. But most of all, I cursed the guidebook – the “Book of Lies”, as it’s jokingly named. The devastating truth of that nickname was hitting hard at that moment. Swallowing the stress (a cornerstone skill of mountaineering), we trekked on, trying to reserve judgement until we could get eyes on the southeast ridge.

When we finally stood on the summit of Outpost and got our first glimpse of the southeast ridge, we allowed some room for cautious optimism. We carefully traced a line down the various sections of the mountain, taking photos for reference. While we couldn’t see the entire descent, we could see about 90 percent of it, and were fairly sure we could make it down without having to set foot on the glacier. Far in the distance, past the sparkling lakes in the Eremite valley, we could see the old valley hiking trail. Just get there, we told ourselves, and we’re home free.

The descent didn’t end up being all that bad – we’ve done worse, in fact. Incredibly loose rock marks the initial summit descent. We stayed just skier’s right of the top of the ridge, and slowly worked our way down over the rock, being careful to stay out of each other’s fall paths. Once we’d passed the steepest terrain, we hit a series of tarns that allowed for faster travel. From here, we then followed a slab ledge series in a zig-zag fashion, essentially looking for easy ramps down, but generally heading south to the toe of the glacier. At the glacier toe, we found a massive ice cave, and many flowing streams tumbling into waterfalls over cliffs into the lake below. A few easy stream crossings (all with perfect little rock bridges, fortunately) took us to the south side of the waterfalls, and from here, an easy and firm slope led down beside a stream to the first alpine lake in the Eremite valley. Perhaps it was the exhilaration that an uncertain mountaineering descent was over, but I was struck hard by the stunning beauty of the alpine lake and valley. Several waterfalls with huge plumes tumbled into a rocky blue lake surrounded by wildflowers, brilliant in the lowering summer sun. I tramped through heather fields after Chris, full of a weary satisfaction that we were only one creek crossing away from the hiking trail we’d spied from the peak. Once we hit that trail, we believed that would be the end of the difficulties of the day.

Traversing east of the lake towards Arrowhead Lake (the second alpine lake up there), we passed Arrowhead on the north side, and encountered a swift stream at its outflow. Our rock-bridge luck had run out unfortunately – this stream was wide, fast, and deep in places, with no obvious place to cross. We scouted the bank for about 15 minutes, and finally settled on a place that seemed safe enough to cross. We took off our shoes and socks, rolled up our pants, and plunged in. Our feet were numb within a minute, and the rocks were horribly slippery, but a very careful and slow crossing did deposit us safely on the other bank, with water never reaching past mid-calf. Shoes on again, and a brief jaunt up the bank left us on the old hiking trail. Hurrah! Our day of misadventure was finally done. Just a simple walk back to the hut on a lovely trail…

We cruised along the trail for a few kilometers, 15 hours into our adventure, discussing our crazy, sometimes nerve-wracking, but truly epic day, until we encountered the last and somehow completely forgotten unknown of the morning: the bridge over Eremite creek. The bridge, about 1 kilometer south of Chrome Lake, was underwater, and the creek itself absolutely raging and completely uncrossable. Our hopes sank as low as that poor wooden bridge. Looking at our topo map, we found ourselves bounded by rivers on either side, with Chrome Lake blocking us to the north, and a large swampy bog covering most of the surrounding areas. We stood there, dumbfounded, soaked in blue evening light in the middle of an infamous Tonquin bog, full of wet grass, deep, sulking mud, and our broken dreams. The third element of misadventure.

I’ll confess, I was completely out of energy and ideas. But Chris, in an adventure-race-style moment of inspiration, found us a path across the swampy bog by tracing a line through bushes and some small trees, which he realized marked firmer ground. We made for the second river on the map, which we had yet to see, hoping that it was possible to cross. We got a lucky break here: it was still and shallow. We found a suitable spot to wade, and again, shoes off, socks off, pants up, and we were across. From here, we skirted around the east shore of Chrome Lake, heading north to strike the ACC hut trail we had hiked the previous day to reach the hut. The edge of the lake was firmer than expected (another lucky break), with only minimal bushwacking in the forest required to circumvent the lake. Finally, we hit the hut trail, and raced along for the final 2 kilometers of our long day as fast as we could, racing the remaining daylight. We hit the hut just before 10 pm, with the last of the light in the sky, beginning the day exactly as we started it: in blue semi-light, and pretty sleepy. Our post-trip celebration was somewhat subdued – a delicious homemade lentil curry in the flickering gas lamp lights of the hut, and then straight to bed!

Our total trip time, including the 3 hour ‘wrong turn’, 6 pitches of rock climbing, 2 stream crossings, a bog-wack, and a bushwack, was 16.5 hours, covering 13 km of terrain and about 1100 m of elevation gain.

While our original itinerary had us climbing Paragon peak the next day, our epic left us desiring nothing more than a rest day. After catching up with the guided group in the morning and swapping adventure stories (they had bailed on Paragon and taken a nap at an alpine lake instead, and were relieved that they didn’t have to call search and rescue to look for us!), we went for a leisurely hike out to Amethyst Lakes to take in the classic view of the Ramparts.

Outpost Peak and its north buttress ended up being a huge adventure of a day, in which good choices, bad choices, and a good measure of luck all played a part. I want to summarize some of the key lessons we learned on this less-than-smooth trip:

• The best descent route from the North Buttress is the one on which the guide took his clients. They found a ramp down from the buttress to the glacier on the west side, then stuck to the gentlest, least-crevassed lines to follow the glacier down and out.

• The “Book of Lies” is a well-deserved name. Do not assume guidebook routes are reasonable just because they’re published in the book (even those labelled as ‘recommended’). Climate change has vastly altered these landscapes – glaciers recede, leaving behind loose and unsettled rock, streams and rivers could be bigger and faster than ever before due to increased melt, rockfall can modify faces, and thinner snowpacks can mean a once gentle snow traverse is now an exposed band of hard, crevassed, and difficult-to-protect ice. Mountaineering is ultimately about self-sufficiency and testing your own route-finding and judgement.

• Ice is king in the Rockies – the snowpack is thinner than the west coast (even in high precip winters), and bare ice on glaciers is common in mid-summer. Don’t sacrifice on ice gear to save weight, especially when hiking into base camp. Make the decision on what to cut once you’ve seen the entire route for yourself, or have some first-hand info from a recent ascent of your route.

• Flexibility is key. It was fortunate that we were familiar with a backup descent route when our original plan did not work. Adequate gear (food, layers, and communication gear) also allowed us to be flexible and extend the expected duration of our day (ie: we had enough to eat, sufficient water, and layers and other items needed to spend the night outside if needed). Also, sufficient alpine skills and experience allowed us to safely retreat (ie: our improvised rappel descent) when we made a mistake (also known as ‘self-rescue’).

While sometimes anxiety-inducing, challenge is a key part of the appeal of mountaineering for us, and Chris and I ended our climb of Outpost peak in agreement: this might have been our favourite trip of the Year of Adventure so far!